How we engineered the user experience design of Elsewhere Sound Space to maximize interaction opportunities for a crowd of thousands while still running a halfway-coherent show.

When a crowd of 10,000 people yell at the same time, does it matter what any of them say?

How can an audience that big contribute to a conversation?

What does it mean to be 'interactive' when the group pushing the buttons are so many?

As creators of both physical installations and web-based experiences, we're used to thinking about either interaction for meatspace users in the dozens, or realtime, often streaming, software experiences that reach viewers in their tens of thousands ... but the idea of combining the two in an interactive experience for a mass audience was new territory.

The context in which we were thinking about this was 2021, mid-pandemic, when we were working with Twitch and beloved Brooklyn music institution Elsewhere to find ways for homebound audiences, hungry for the community and togetherness of live music, to connect.

At the time, virtual production-powered concerts were everywhere; virtual festivals were taking place in browser windows, well-known musicians were represented in machinima extravaganzas in Fortnite, and even simple livestreams felt especially poignant and special.

But none of these approaches offered a real sense that the show you were watching was different because you - one specific, dedicated fan - were there. It's not really possible to feel seen in a traditional one-to-many streaming audience. That’s a broadcast.

And while meaningful interaction could be a great thing to offer a huge crowd, if every fan gets to come up and touch Rod Stewart's hair, he's either not going to get a lot of singing done or there can't be all that many fans doing the touching.

If we tap the glass, we want the fish to look at us, then go back to doing fish stuff.

It was from this perspective that we began thinking about what's possible with bidirectional communication in a live performance when the show is led by its tech team.

[The result was Elsewhere Sound Space <— check that link if you just want to read about the show - this post is about the interaction design behind the show.]

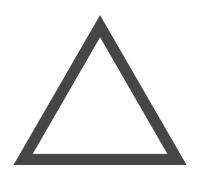

The Disruption Pricing Principle: A Framework for Mass Interaction

This chart and the axes it posits are the main idea behind this post. Don’t worry about the specific interactions plotted here - they’re explained below. Just pay attention to the axes and the implications of the various regions of the space described.

The framework we came up with plots viewer-initiated interactions on axes from 'cheap' (easy to trigger) to 'expensive', and on the other axis, from unobtrusive to disruptive.

The theory is simple: viewers get a thrill from being a part of the show, and that thrill is proportional to how much influence their action has on the events taking place onscreen. Constraining this is the idea that the amount of this excitement available to viewers is finite - the more presence in aggregate viewers have in the developments onscreen, the more the show becomes about viewer involvement, and the less value any viewer interaction has.

Shows that index heavily in this direction can be hilarious and thrilling and groundbreaking in their own right, but they feel more like a video game, where the audience is almost puppeting the talent onscreen, and in that context, getting a response from interaction is so expected as to feel almost mundane once you get used to it. Keeping this tension in balance — optimizing the utility of viewer interactions while still having the show be about something else — is the mechanic we’re investigating.

In order to ‘price’ interactions appropriately, actions that are especially disruptive to the show should be challenging to effect, whereas actions that have little to no effect on the show shouldn't take a lot of effort or money. Things that live outside of those two quadrants of the chart will either be too easy to abuse and thus frequently disruptive to the show (cheap and disruptive - eg hecklers) or disappointing for the viewer (expensive and underwhelming - eg VIP tickets for a 1-second meet and greet).

We should clarify here that while 'disruptive' is generally a negative term, in our case the show was intended to be a gonzo experience thematically, aesthetically, and technically, and show-derailing interactions from the audience, while disruptive to the furthering of the gonzo plot, can be hugely fun and are crucial in fostering the giddy feeling that the onscreen talent might look into the camera and speak directly to you at any moment.

That’s that ‘tap the fishbowl’ feeling we were after, but the effect diminishes with the frequency with which it’s seen.

We want the fourth wall there so when we break it, it counts.

In the interest of making it so as many audience members as possible can have a hand in initiating these kind of rewarding interactions, we looked to offer a blend of options that felt to viewers like they could participate in any fashion from casually, as a crowd member, to aggressively, as a super-fan, much as they would in a rowdy live audience.

Let's look at some of the interactions we built, starting small and working our way up:

CHEAP and UNOBTRUSIVE

Chat Interactions

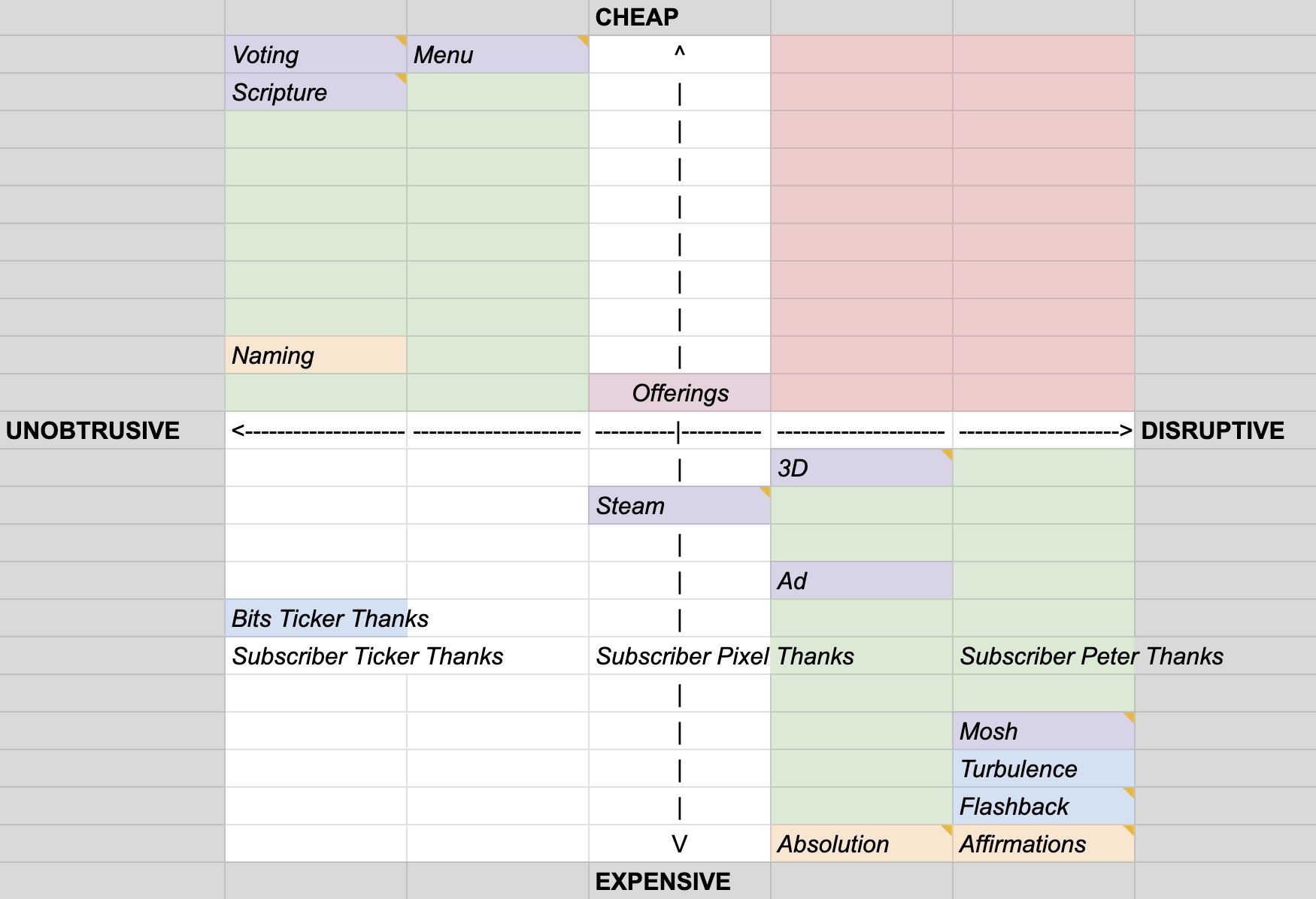

On Twitch, 'the chat' is a character in every show, and it's the main channel through which audiences and on-screen talent interact. It's become a convention in some of the more graphics-heavy Twitch shows to put the actual chat onscreen in order to provide a diegetic explanation for the talent's sightline when reading from an in-studio monitor.

The chat was sometimes literally onscreen.

It's also an easy place to sprinkle in opportunities for viewers to drive unobtrusive interactions, including automated responses to user keyword commands, whether in the open channel or as a DM. We offered a few chat-based bang commands, like '!scripture', which viewers could use to dredge up bits of lore, backstory, and color writing from the enormous database to which we were constantly adding.

Having the voice of the show reinforcing tone in the chat, seemingly in dialogue with viewers, provided high ROI for an ongoing process of populating the response databases with tidbits as they occurred to us.

Time-Limited, Binary Voting

(choose your own adventure)

As a visually rich virtual production improv show, the settings in which we placed our talent were key to driving story and conversation forward — in reality, our talent were standing in separate rooms facing a camera and a whole bunch of monitors, one of which was showing the composited scene, one the chat. To that end, our hosts would often put the choice of a change of scenery to the crowd, triggering a timed vote in which the majority won.

This is our first example in a category of interactions designed to let a large group of people each individually participate in a collective action that has more weight in the proceedings of the show than we'd want any single viewer to have.

Viewers chose the next location for the action.

This interaction was also used to allow the audience to weigh in on subjective decisions that directly affected the plot. In the case of the image below, it was to determine the winner of a key debate for Space President:

A vote to determine the winner of a debate between the challenger and incumbent in the race for Space President.

Onscreen Easter Eggs

Just seeing your name on screen can be rewarding, so we looked for easy ways to make that happen whenever possible. In the case of the Mud Bath scene, viewers who looked around in the “!menu” command or who saw other users doing it would notice that they could type “!steam” in the chat, releasing a burst of steam with their name spelled out in it and raising the temperature on the onscreen thermometer, which slowly fell between bursts. Their username name would rise with the steam and collide with the ceiling and walls of the bath before dissipating.

The rate of this interaction was gated by the temperature in the room. Once over a threshold of some 330K (about 135F), viewers who tried to use this interaction were told by the chat responder-bot that they needed to let the room cool a bit before adding more steam.

Usernames emitting from steam bursts triggered by those users.

Judged Submissions

Each episode included a long-running interaction, promoted at intervals via onscreen text, reminders in the chat, and occasionally by the talent themselves, asking viewers to come up with a new name for the guest in the event that they were indoctrinated into the cult at the end of the episode - another thing that was put to a vote.

Names entered this way (purchased with 'channel points' — more on this below) went into a database that was reviewed off-camera by the show crew, who manually picked a winner for the host to announce at the end of the episode, along with acknowledgement of the viewer who suggested it.

A viewer is acknowledged for contributing the winning cult name for the guest, as judged by the offscreen crew.

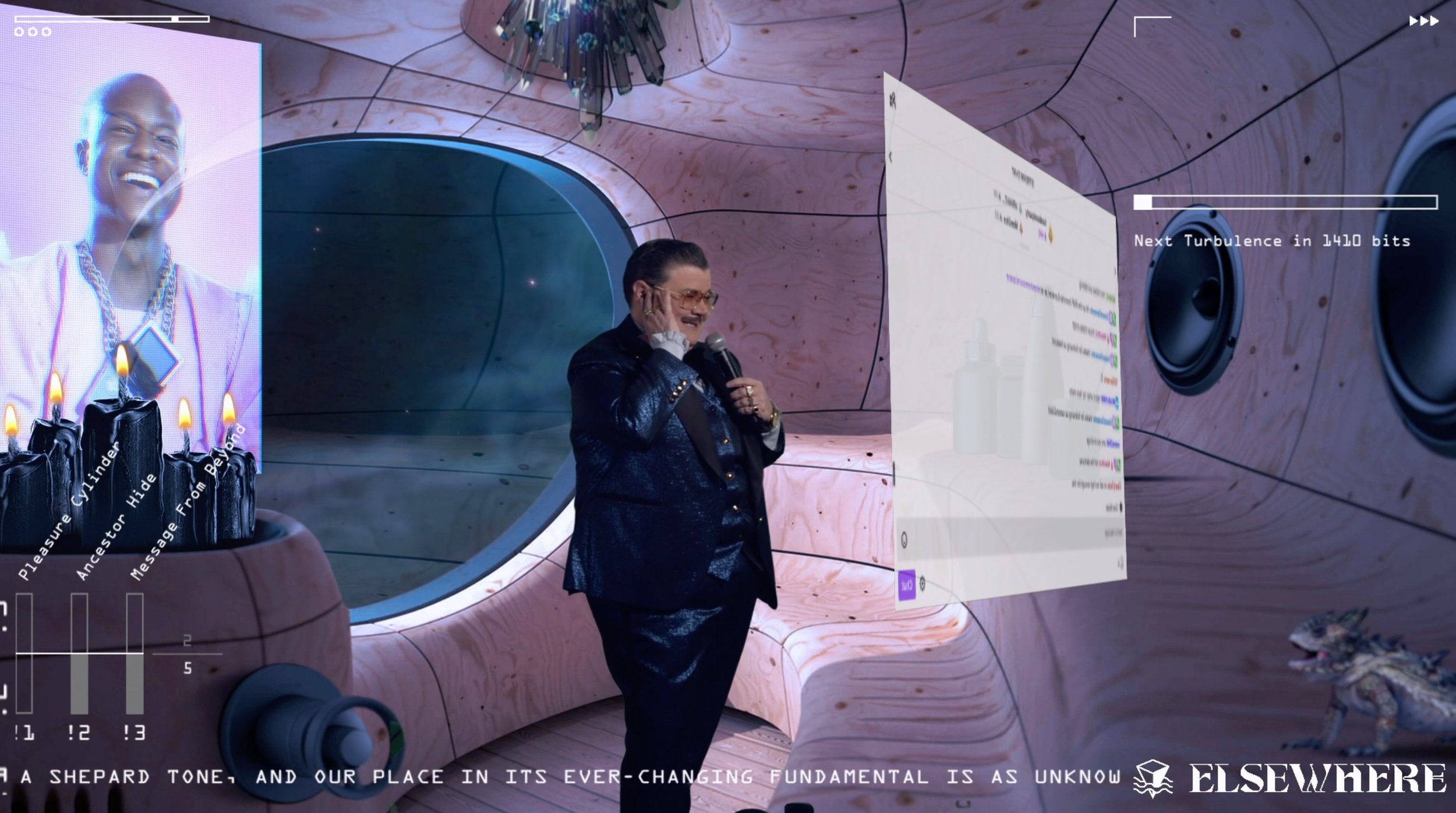

Dynamic Credits

We took advantage of the ability to dynamically generate the credits just before they went onscreen to make sure every subscriber and contributor was acknowledged and the top contributors were surfaced too.

Stats about top contributors calculated at credit runtime.

A list of current subscribers, updated just before it went onscreen.

We also hyped a 'Soul Match' gag repeatedly throughout the show, held until the very end of the credits, in which anyone who contributed to the show during the episode was entered for a chance to match with another contributor, or, if they were extremely lucky, with The Founder of the cult - a semi-conscious cadaver who is currently in cryo suspension and only communicates through a receipt printer.

Worshipper internetexplorer matched with THE FOUNDER!!

RIGHT in the MIDDLE

(not too intrusive, not too expensive)

You’d think this category would be where we focused most of our interaction efforts, but most of our ideas were on the more extreme ends of the spectrum. With that said, voting in the ‘offerings’ gag below was likely the most common action taken by any given user.

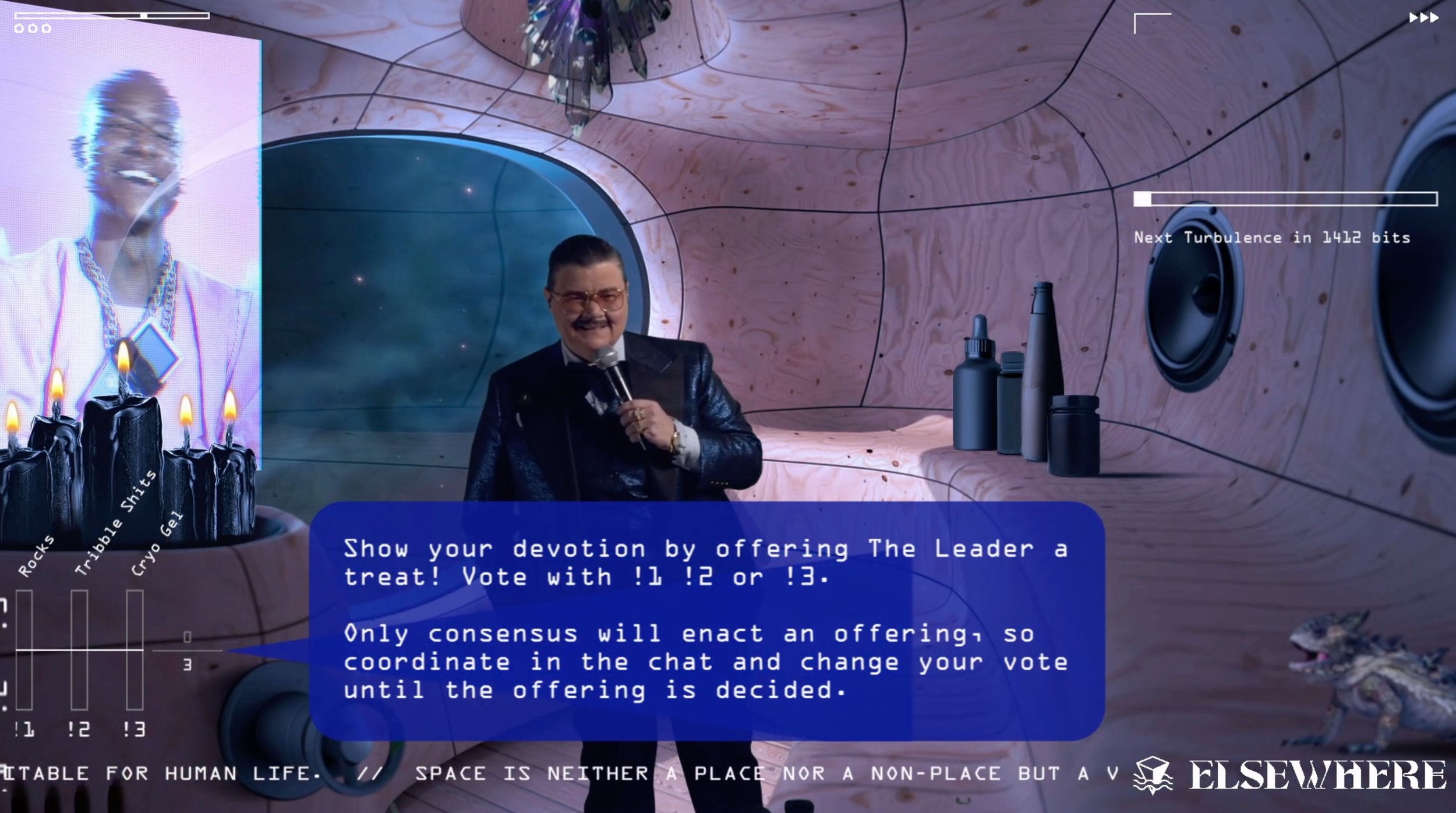

Parimutuel Voting

(Offerings)

Onscreen tool tip tutorializing the offering mechanism. These kind of tips were crucial to bringing the audience along with the operation of the various interfaces around the show without requiring the Leader to break the fourth wall and confront the interaction mechanism in a way that didn’t feel funny or fun.

As an enticement to spontaneous audience coordination towards a common goal, we implemented a 'parimutuel voting' system, in which viewers could assign and re-assign their vote at any time among three options, but the decision event wasn't triggered until a certain number of total votes was cast, and until a certain percentage of those votes was cast for a specific option. This required some consensus-building.

The worshippers have offered the Leader some Hyper Mist

When these threshold numbers were large, it meant that viewers had to coordinate in the chat to align opinion around a specific (often ridiculous) choice - in this case among sight-gag prop jokes framed as 'offerings' to the Leader. When the threshold was reached, a sound and title package would overwhelm the frame, insisting that the Leader (and the guest, if they were on camera), accept the offering of their followers by enjoying a Pleasure Cylinder, or a Cryo Gel, or some Hyper Mist, or Rocks, or a Dark Secret, etc. Prop comedy ensued.

Ads

An ad for something called ‘Success Tabs’, triggered by viewer stephalope’s tip

A simple way to gate the rate at which viewers take somewhat obtrusive onscreen interactions is to literally price them, in dollars, or, in the Twitch world, in a currency called 'bits', which cost dollars to buy.

The idea of onscreen ads paid for by viewers seemed like a good reward for a nominal contribution of around a dollar, so at any time a viewer could 'buy' an 'ad' for a random product they didn't know in advance, and the ad bubble would appear and float up over the action, featuring some randomly-selected ad copy and their username.

DISRUPTIVE and EXPENSIVE

On the very disruptive and expensive end of the interaction spectrum, we had options in both collaborative action and individual action mechanisms.

Bit Meter: Aggregate Tips

At all times in which the show was open for interaction, which was any time the musical guest wasn't performing or saying something especially personal, there was a meter in the top right of the screen charting the audience's progress towards triggering a disruptive action. The meter was moved along via bit contributions (monetary tips) to the show, and when it filled up, it triggered one of a few actions, usually every 30 minutes or so.

A favorite was the 'Flashback', where the screen would go black and white and wavy (classic flashback effect) and the host would be overcome with an often painful and bizarre improvised memory from the show's backstory.

Next tip of 96 or more bits kicks off the flashback.

“Oh! Ohhhhh!! I’m suddenly remembering my father’s accountant, Sol … god he was a terrible accountant!”

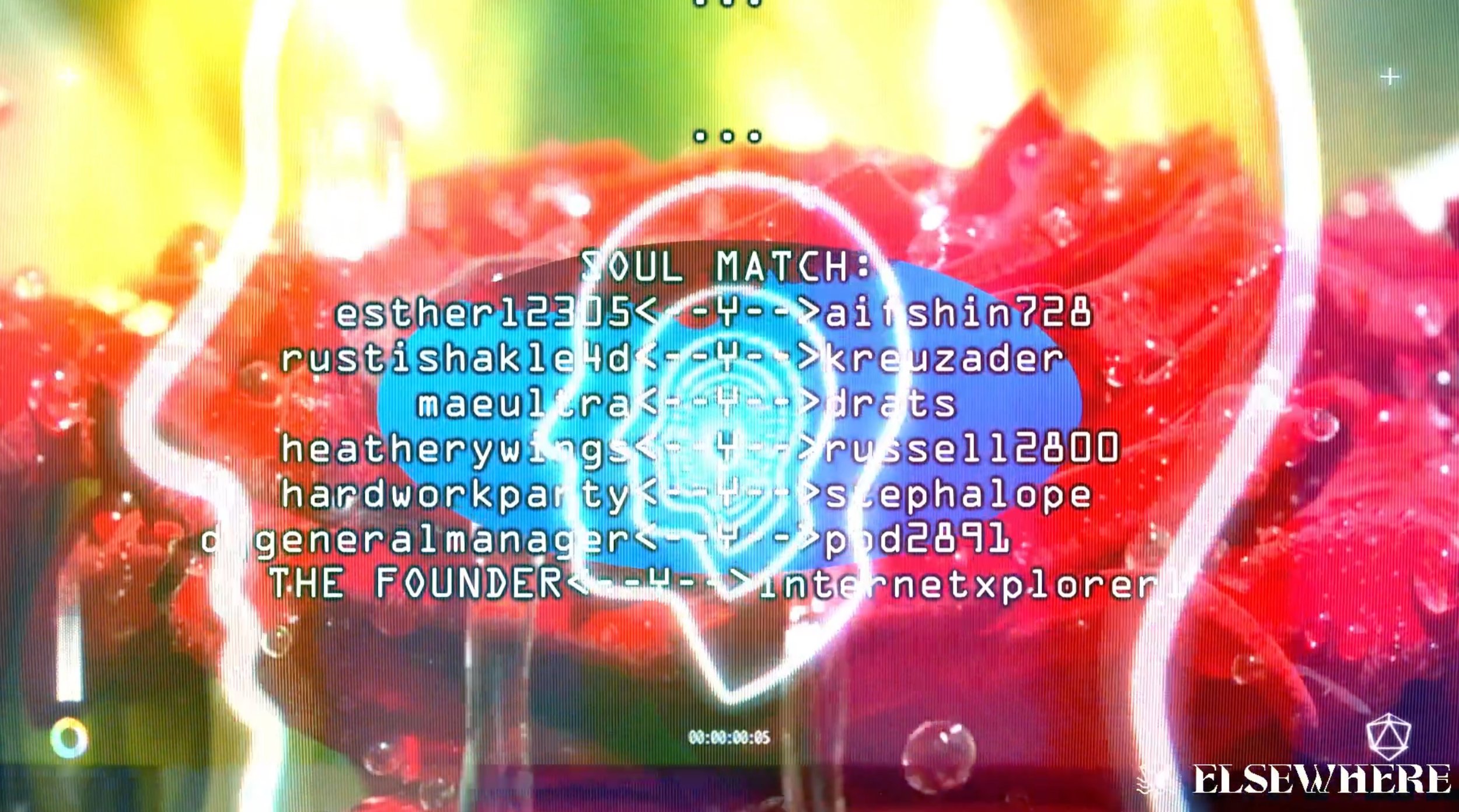

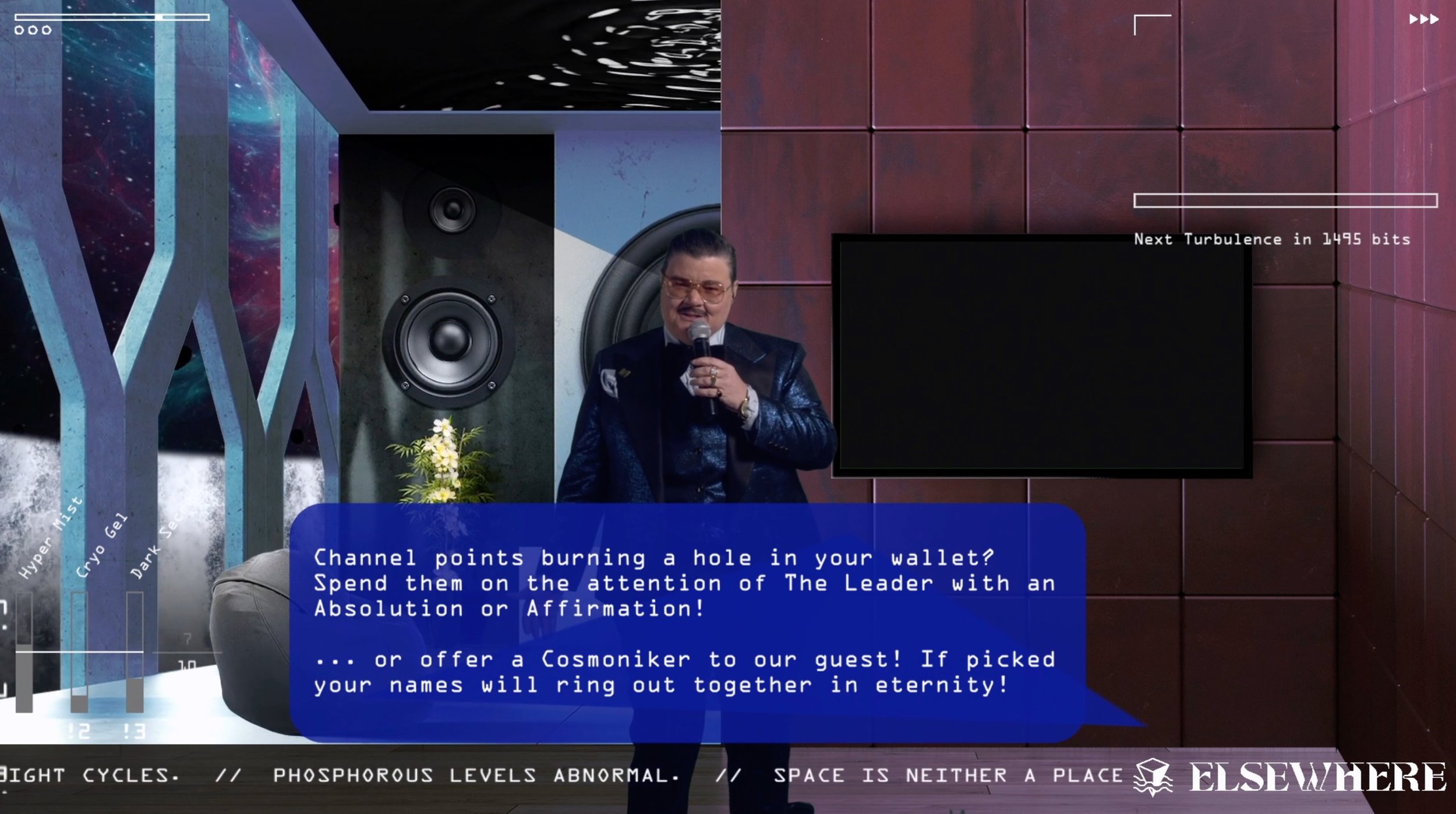

Absolution and Affirmations

The two most show-stopping interactions a single user could trigger were the Absolution and the Affirmation. Users could only invoke these effects by spending a large amount of 'channel points', a kind of loyalty points Twitch viewers accrue on a channel-specific basis. This is a currency the channel administrators can choose if and how to allow the viewer to redeem, and for what.

In our case, viewers could spend a large number of channel points - an amount it would take a very active participant almost an entire episode's worth of engagement to accrue - in order to purchase from the leader an Absolution or Affirmation. This was deliberately priced at a level that was only attainable by serious fans who were willing to invest a lot of their slowly-earned channel points into one big action.

The Affirmation was conceived as a sincere response to the psychic turbulence of the real-world moment, intended as a beat where the Leader, speaking directly to the viewer, calling the viewer out by username and looking directly into the camera, would tell them that they are OK - that they are good enough the way they are, and that they are loved, filtered through an intense, throbbing color LUT and a tunnel-vision blur effect.

The Absolution was a similar gag, although delivered in a more tongue-in-cheek fashion, in the style of a megachurch preacher, where the viewer would purchase absolution for a specific sin they described at the time of purchase.

In both cases, the actor playing the Leader would see the username and the Affirmation or Absolution (and the sin requiring Absolution) waiting in a queue on their HUD screen, and as soon as they could get to it, they'd begin the acknowledgement and the TD would trigger the effect let the moment take over the show.

In addition to verbal exposition from the host and reminders from the moderators in the chat, occasional onscreen tips would guide users to purchase Absolutions and Affirmations.

An Absolution for viewer seansatomusic

Wrap

There’s more to cover but we hope you get the idea of how we applied the framework to our strategy in a way that enabled as many viewers as possible to experience the frisson of having the TV talk to them while still running a (barely) coherent show.

If you’d like to read more about the production, check out our case study here. If you’d like to see us make more Elsewhere Sound Space, help us find a sponsor!! Seriously, we need a sponsor.

If you’d like to read more about the tech behind the production, we did a couple of long-form interviews on the topic and the videos are linked in this blog post.

If you’d like to make another show like this with us, reach out. We’d love to spend all our time making this show or something equally wild and ground-breaking.